Adventures in Researching a Unique Whale Tooth

A Collections Chronicles Blog

by Michelle Kennedy, Collections and Curatorial Assistant

July 16, 2020

One of the best parts of being a collections specialist is that I get to work with, care for, and research the incredible collections and archives at the Museum. This means I get to learn something new almost everyday!

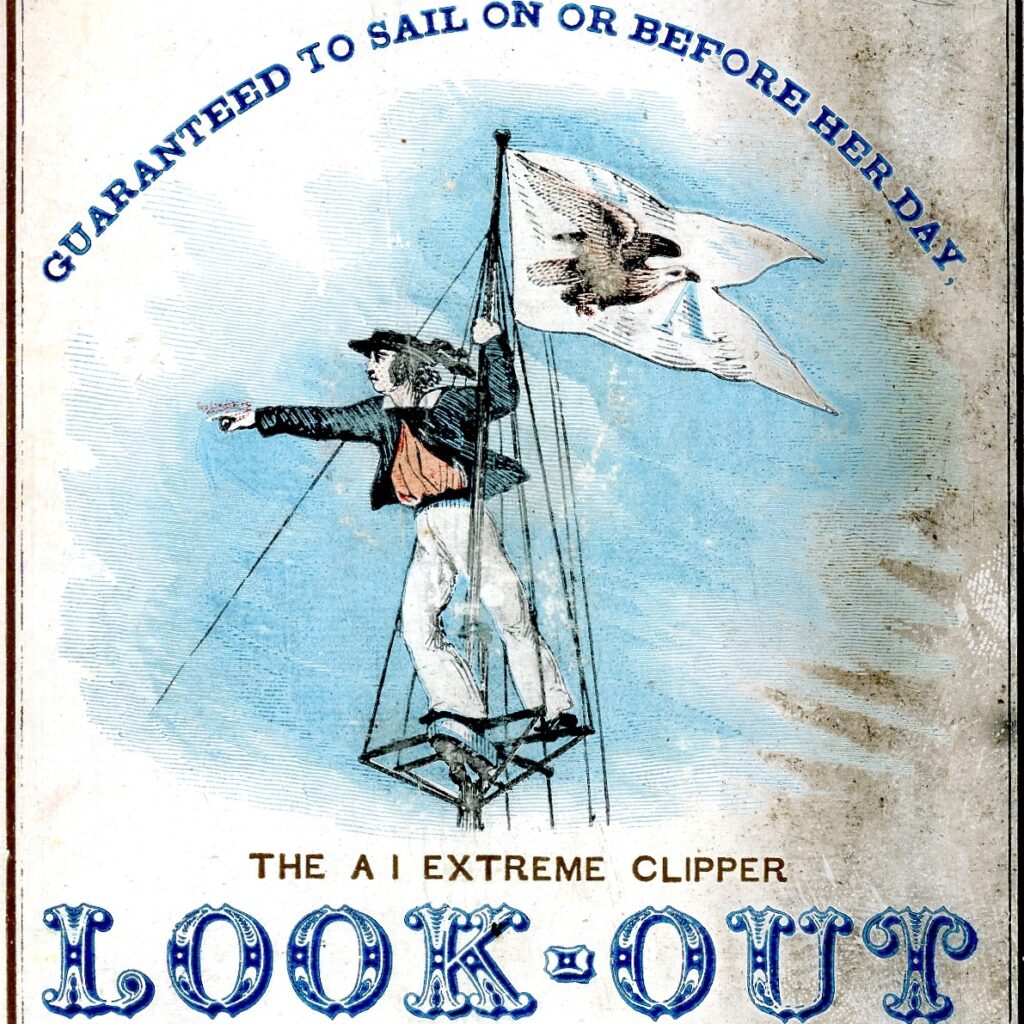

Maybe you’d guess (correctly) that I’ve learned a little about sailing, a little about letterpress printing, a little about ocean liners…but sometimes a collection throws you into a topic you never thought you would look into.

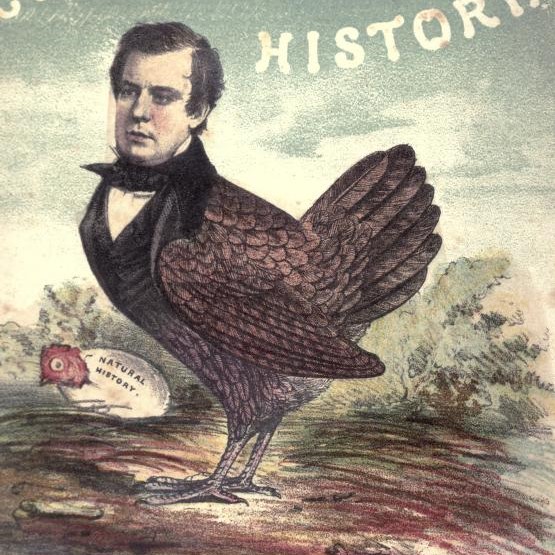

Today, I’m going to talk about this scrimshawed whale tooth…featuring a chicken with a man’s head (or is it a man with a chicken’s body?) and how I attempted to decipher its significance and inspiration.

*Spoiler* I didn’t conclusively solve this mystery, but I think this post provides insight on how the collections department researches our unique collection.

Museums document the historical context of their collections so that they can use the objects to interpret history with the public. If you’ve ever read an exhibition label, a collections-based social media post, or even watched an episode of Travel Channel’s “Mysteries at the Museum,” you’ve experienced how artifacts can be used to connect to the past.

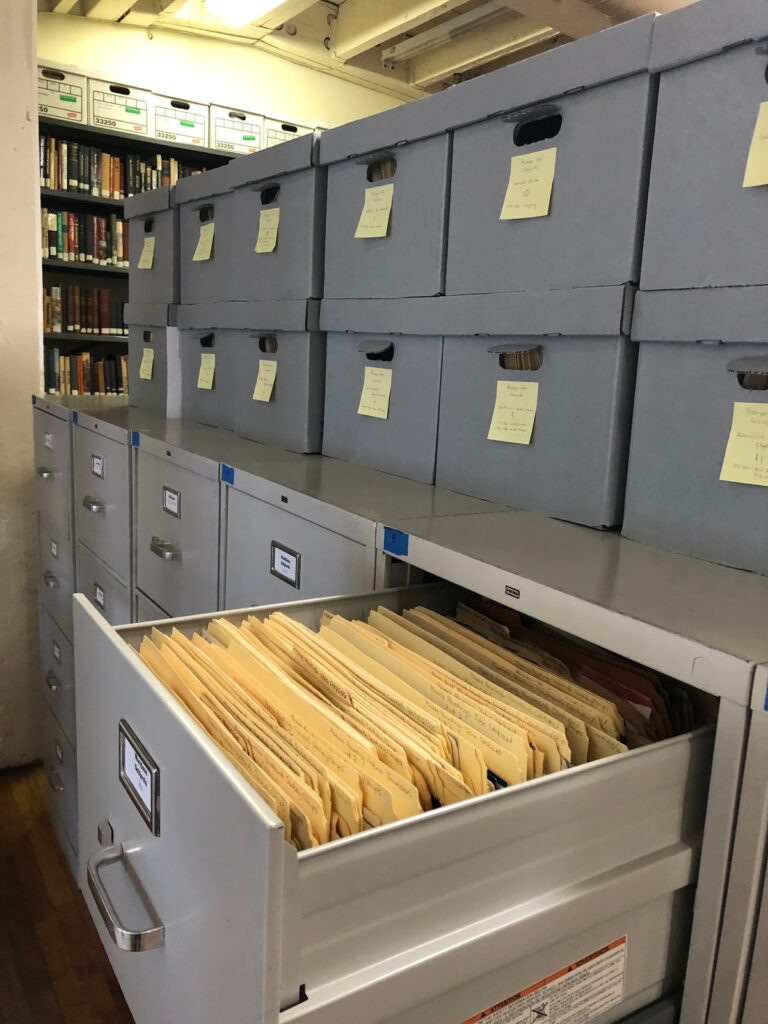

My responsibilities include archiving and digitizing what historians and past curators have written about our collections objects, along with looking for contemporary sources and doing original research when needed.

For most objects, I’m only trying to find evidence to solve one of the usual mysteries: who the artist/maker is, when the object dates to, and/or where it came from.

But sometimes…an object asks you to look a little deeper. Sometimes you are asked “what does the chicken-man mean?”

Before rushing to find books about scrimshaw and the symbology of man-headed chickens in the 19th-century, I had to do the basics: examining the object.

You never know what kind of information could be hiding in plain sight. By looking closely, sometimes you can find an overlooked maker’s mark, inscribed date, or past inventory number.

Unfortunately this whale tooth didn’t have anything like that, but I carefully noted what I could see:

“Whale tooth, engraved with a bird with a man’s head, facing left. Figure is wearing a brimmed hat with ribbon and a sash diagonally across the chest. Head includes mustache and full beard. Figure is holding a long object that flares at one end under one wing. Feet in mid-stride. Pin point style. Two flowering branches crossed beneath. Back is blank”

I had a couple “follow-up” questions about the tooth after looking at it more closely; could we possibly identify the hat the chicken-man is wearing? And what is the object under the wing?

But again, before looking for sources on 19th- century headwear, I had another object to look at. This tooth was one of a pair.

As strange as the chicken-man tooth was on it’s own, its mate only made things more bewildering. To explain why, let me tell you the third step in my process: comparing the object to others in the collection.

The Seaport Museum collection includes over 400 pieces of scrimshaw. In the briefest terms, scrimshaw is a form of folk art practiced by whalemen from around the second quarter of the 19th century until the early 20th century. Usually made by whalers at sea, scrimshaw is often made by engraving designs on whale ivory and bone. Scrimshaw also includes carved and built-up “utilitarian” items such as canes, pie crimpers, clothespins, ditty boxes, and more.

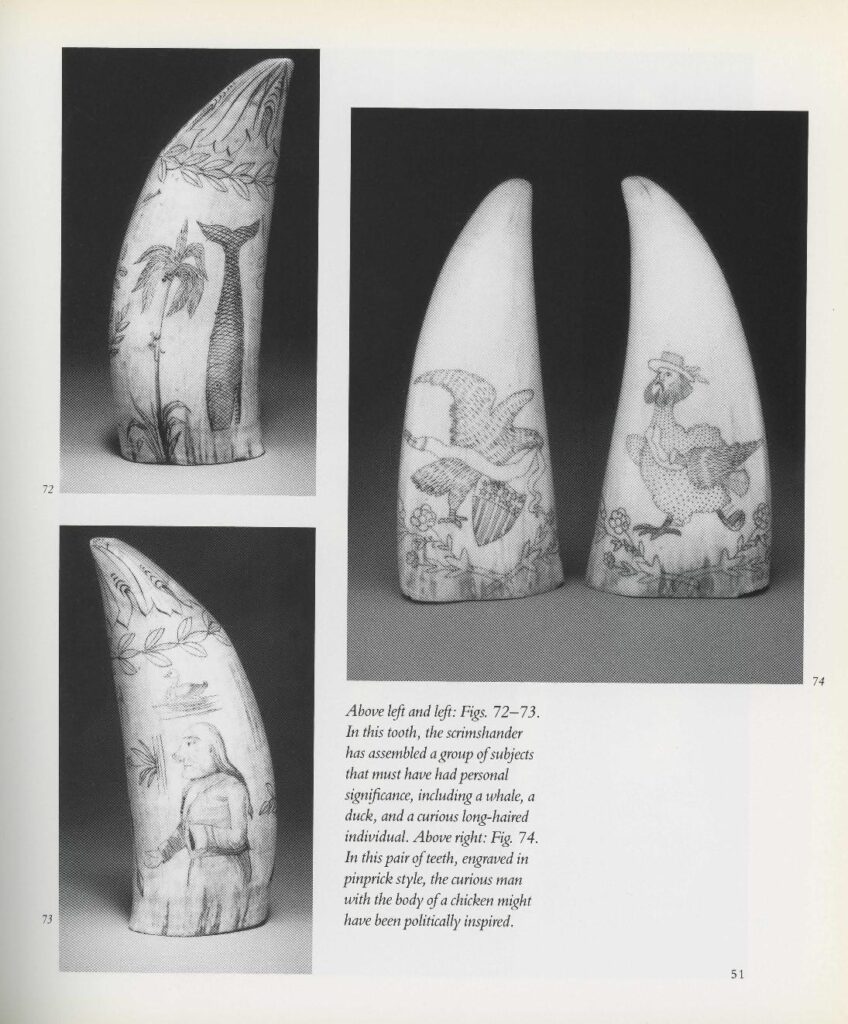

Some of the most common motifs on scrimshaw are what you might expect; ships, whaling scenes, women, and patriotic motifs like American eagles. This pair of whale teeth includes one very conventional American eagle…and one chicken-man. Unsurprisingly, there is no other design like it in our collection.

Though the Museum holds an impressive collection of scrimshaw, I looked at other museum collections to see if I could find something comparable at another institution. I didn’t have any luck- but shout out to Mystic Seaport Museum for getting close with their “Sperm whale tooth, standing man, dressed chicken tooth, 1957.707” which features a chicken wearing clothes.

Once I had looked for possible related objects to my research subject, and collected my follow-up questions, it was time to look at the past documentation of the object. There are two kinds of Museum records I usually look through when researching a collection object: published and internal. Internal documents are things that the public never sees, like correspondence with donors, appraisals, and condition reports done by staff. Published documents are exhibition labels, books, magazine articles, and social media posts. When looking for more in-depth research into an object (like looking for an image’s meaning), published records are often more helpful since it’s more likely to have curatorial interpretation.

The goal of almost all collecting institutions is to have its records digitized and easily searchable for researchers and collections staff in a collections management database. Like a lot of museums we’re still working on getting through our backlog of half-a-century worth of collections documentation. I often have to dive into the hard copy records during my research.

I found a publication featuring our chicken-man scrimshaw. The tooth was in an exhibition “A Mariner’s Fancy: The Whalemen’s Art of Scrimshaw”, which was on display from 1991-1993. The accompanying book describes the teeth as “…engraved in the pinprick style, the curious man with the body of the chicken might have been politically inspired.”[1] “A Mariner’s Fancy: The Whaleman’s Art of Scrimshaw” by Nina Hellman and Norman Brouwer, 1992, p. 51

This line dovetailed with another document I found in the tooth’s hard-copy file; a 1990 survey by a scrimshaw expert noted that the pair of whale teeth came “…from the same whale jaw; ‘chicken’ illustration similar to cartoon showing Chester Arthur’s face upon a chicken’s body; probably after a political cartoon (possibly T. Nast)”

This 1990 analysis touches on the fact that the designs engraved on scrimshaw were often borrowed from popular prints and illustrations.[2] “To Swear Like a Sailor: Maritime Culture in America, 1750–1850” by Paul A. Gilje, 2016 p. 55 It was entirely possible that chicken-man could be traced to a contemporary political cartoon. If I found the print the tooth was based on, it would allow us to really narrow down the time period it was made and tell us a bit more about the maker and the publications available to them. It could even give us the original context of chicken-man, even if the tooth itself was a re-interpretation.

With the leads provided by past experts, I was hoping that I might find a matching illustration using the incredible power of the digital keyword search. There have been times I’ve been able to solve a collections mystery that my predecessors couldn’t simply because I have access to Google Image search.

Circling back to my original description of the tooth, I wanted to look again at the few details I couldn’t identify right away—the chicken-man’s hat and the object under his wing. The hat resembled a sailor’s straw hat with a long ribbon, known as a sennit, which was worn during the 19th century. [3] “Royal Naval uniform: pattern 1910,” National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London

The object under the chicken-man’s wing could also be nautical since it resembles a speaking trumpet— a type of megaphone used aboard ships to project a master’s or officers orders to the crew. [4] “Ship’s Speaking Trumpet, Bark Laura, 1858,” National Museum of American History

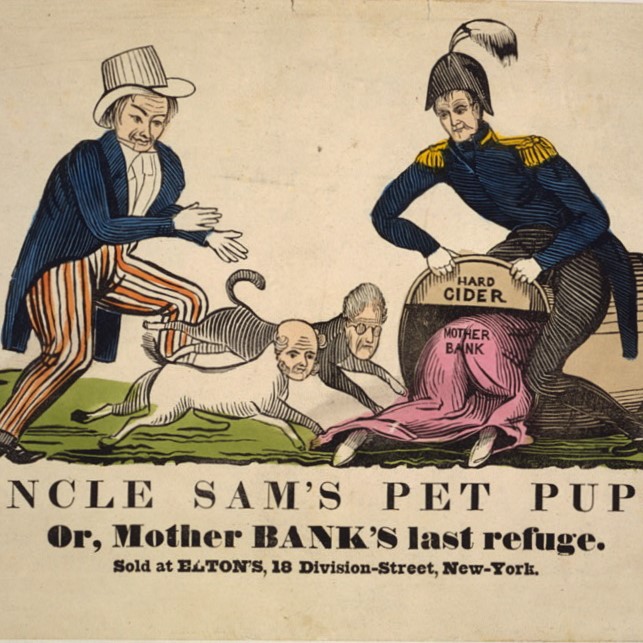

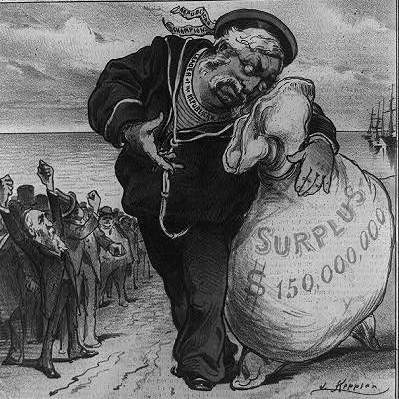

With a few more possible keywords from the whale tooth’s image I searched for cartoons related to sailors, political cartoons of Chester A. Arthur by Thomas Nast, and general mid-19th century use of human heads on animals. I learned a lot, and found some amazing objects I would never have thought existed, but I did not conclusively find a match for this particular scrimshaw. [5] “The comic natural history of the human race” by Stephens, H. L. (1824-1882), University of California Libraries

University of California Libraries

American cartoon print filing series, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

American cartoon print filing series, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

It’s entirely possible that the design of chicken-man was original to the maker. It could even be a caricature of a fellow sailor or one of the ship’s mates. Though there is certainly more to look into, and I had to wrap up my brief research without finding a definite answer, I am still happy to have gone down the rabbit hole presented by this unique object.

Explore the Collections

Through the new and improved Collections Online Portal, you can explore highlights from the various collections within the Museum. Whether items are preserved in storage, displayed in Museum galleries, or on loan to fellow institutions, you can digitally discover some of these special objects in digital format.

References

| ↑1 | “A Mariner’s Fancy: The Whaleman’s Art of Scrimshaw” by Nina Hellman and Norman Brouwer, 1992, p. 51 |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | “To Swear Like a Sailor: Maritime Culture in America, 1750–1850” by Paul A. Gilje, 2016 p. 55 |

| ↑3 | “Royal Naval uniform: pattern 1910,” National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London |

| ↑4 | “Ship’s Speaking Trumpet, Bark Laura, 1858,” National Museum of American History |

| ↑5 | “The comic natural history of the human race” by Stephens, H. L. (1824-1882), University of California Libraries |